Non è una vergogna diventare ricchi. Ma è una vergogna morire ricchi. Andrew Carnegie.

INVENTORI E GRANDI IMPRENDITORI

In questa corposa sottosezione illustro la vita di quei grandi capitani d'industria e/o inventori che hanno sostanzialmente contribuito al progresso industriale del mondo occidentale con particolare riguardo dell'Italia e del made in Italy. Anche con riferimento alle piccole e medie imprese che hanno contribuito al progresso del Paese.

Biografie

A - Abarth - August Abegg -

Adamoli - Giovanni Agnelli - Franco Angeli - Agusta - Alemagna - Amarelli - Amato - Angelini - Ansaldo - Aponte - Richard Arkright - Arnault - Astor - Auricchio -

B - Barilla - Barovier - Bastogi - Beneduce - Karl Benz - Beretta - Bertone - Bettencourt - Bialetti - Bianchi - László József Bíró - Coniugi Bissel - Bocconi - William Edward Boeing - Bombassei - Bombrini - Borghi - Borletti - Bormioli - Borsalino - Bracco - Branca - Breda - Brugola - Brustio - Buitoni -

C - Cabella - Campagnolo - Campari - Cantoni - Caproni - Caprotti - Cargill - Carnegie - Cassani - Louis Chevrolet - Cicogna - Cini - Cirio - André Gustave Citroen - Colussi - Costa - Cosulich - Crespi - Cristaldi -

D - Gottlieb Daimler - Danieli - De Angeli - De Cecco - De Ferrari - Rudolf Diesel - Walt Disney - Donegani - Ennio Doris - Cavalieri Ducati - William Durant -

E - Thomas Edison - Erba -Esterle -

F - Enrico Falck - Fassini - Fastigi - Feltrinelli - Anna Fendi - Ferragamo - Ferrari - Ferrero - Ferruzzi - Figari - Florio - Henry Ford - Enrico Forlanini - Frick - Fumagalli -

G - Egidio Galbani - Edoardo Garrone - Peter Giannini - Giuseppe Gilera - Giugiaro - Gobbato - Francesco Gondrand - Riccardo Gualino - Gucci - Carlo Guzzi -

H - Hewlett e Packard - Ulrico Hoepli - Huntington -

I - Ferdinando Innocenti -Isotta e Fraschini -

J - Steve Jobs

K - Koch - Krizia - Raymond Albert Kroc - Alfred Krupp

L - Lamborghini - Vincenzo Lancia - Vito Laterza - Lauder - Achille Lauro - Lehman - Roberto Lepetit - Mattia Locatelli - Florestano de Larderel - Luigi Lavazza -

M - Macchi - Marchetti - Marelli - Marinotti - Mars - Martini - Maserati - Marzotto - Mattei - Melegatti - Menada - Menarini - Merloni - Merrill - Fratelli Michelin - Miller - Mondadori - Montesi - Morassuti - Angelo Moratti - Morgan - Angelo Moriondo - Angelo Motta - Giacinto Motta - Ugo Mutti -

N - Giuseppe Nardella - Nardi -Vittorio Necchi - Nobel -

O - Adriano Olivetti

P - Pagani - Parano - Pavesi - Peretti - JL Périn - Perrone - Pesenti - Armand Peugeot - Piaggio - Pininfarina - Pirelli - John Pemberton - Pomilio - Stephen Poplawski - Ferdinand Porsche- Prada - P&G -

R - Guglielmo Reiss Romoli - Louis Renault - Alberto Riva - Angelo Rizzoli - Agostino Rocca - Gianfelice Rocca- John Davison Rockefeller - Nicola Romeo - Alessandro Rossi - Rothschild -

S - Angelo Salmoiraghi - Savoia e Verduzio - Isaac Merrit Singer - Alfred Sloan - Solvay - Luisa Spagnoli - Otto Sundbäck

T - Franco Tosi - Troplowitz - Nicola Trussardi -

V - Gianni Versace - Vittorio Valletta - Vanderbilt - Alfredo Vignale - Carlo Vichi - Giuseppe Volpi

W - Walton - Edoardo Weber

Z - Ugo Zagato - L. Zambeletti - Lino Zanussi - E. Zegna

John Jacob Astor I

1. Astor sperimentò diverse attività prima di entrare nel business delle pellicce.

Dopo aver lavorato per diversi anni al fianco del padre nell'azienda lattiero-casearia di famiglia, Astor lasciò la Germania all'età di 16 anni per raggiungere il fratello a Londra. Per cinque anni aiutò suo fratello a produrre e vendere strumenti musicali, per poi recarsi negli Stati Uniti nel 1784 per servire come agente statunitense dell'azienda. A 21 anni, secondo quanto riferito, Astor portò con sé poco più di un carico di flauti. Una volta negli Stati Uniti, Astor lavorò con un altro fratello maggiore, Henry, un macellaio di successo nella zona di Bowery a New York, e poi per poco tempo come fornaio. Disilluso da tutte queste attività, Astor iniziò a commerciare in pellicce con le tribù locali di nativi americani e quando un trattato commerciale tra gli Stati Uniti e la Gran Bretagna aprì nuovi mercati nell'ovest nel 1790, Astor entrò in azione.

2.Perse la sua fortuna durante la guerra del 1812.

All'inizio del 1800, Astor espanse la sua attività, stabilendo rotte commerciali verso la Cina e l'Europa, ma quando l'Embargo Act del 1807 portò alla chiusura di molti porti europei alle navi americane, Astor si rivolse a ovest per nuove opportunità. Nel 1808 aprì la prima di numerose aziende di pellicce, l'American Fur Company, seguita subito dopo da filiali tra cui la Pacific Fur Company. Nel 1811, la Pacific Fur Company fondò Fort Astoria (in quella che allora era una regione contesa nota come Oregon Country), il primo insediamento americano sulla costa del Pacifico. La presa di Astor sul commercio di pellicce della regione non durò a lungo: quando scoppiò la guerra tra Stati Uniti e Gran Bretagna nel 1812, gli uomini di Fort Astoria furono presi dal panico, vendendo l'attività e le sue partecipazioni a una società con sede in Canada. I loro timori erano fondati: pochi mesi dopo arrivò una nave da guerra britannica con l'intenzione di occupare il forte. I sogni di nord-ovest di Astor erano a brandelli e gli inglesi avrebbero mantenuto il controllo dell'avamposto per i successivi 40 anni.

3. Astor chiese aiuto al governo degli Stati Uniti per riprendere la sua ttività nel mondo delle pellicce.

Dopo la fine della guerra nel 1815, Astor fece pressioni con successo sul Congresso degli Stati Uniti per una serie di progetti di legge volti a impedire il ripetersi di perdite finanziarie nel nord-ovest. Quando il Congresso approvò un disegno di legge del 1816 che vietava ai cittadini non statunitensi di possedere aziende di pellicce nel territorio degli Stati Uniti, la stessa società canadese che aveva acquistato Fort Astoria fu costretta a vendere tutte le proprie partecipazioni ad Astor. Sei anni dopo, Astor ricevette ulteriori aiuti dal governo degli Stati Uniti quando il Congresso votò per chiudere tutte le sedi commerciali gestite da governi stranieri, lasciando ad Astor il monopolio sul commercio di pellicce.

4. Astor fece fortuna anche contrabbandando droga.

Mentre le sue pressioni sul Congresso continuavano, Astor distolse brevemente la sua attenzione dal commercio di pellicce. Nel 1816 acquistò 10 tonnellate di oppio dall'Impero Ottomano e lo spedì a Canton, in Cina, a bordo di una delle sue navi dell'American Fur Company, nonostante il divieto di importare droga da parte della Cina. Dopo aver ricavato un buon profitto dall'impresa illegale, Astor interruppe il suo coinvolgimento in quell'attività nel 1819. Astor fu il primo americano a trafficare la droga in Cina, ma certamente non l'ultimo: molte delle prime fortune americane furono costruite sul commercio cinese di oppio, tra cui quello di Warren Delano Jr., il nonno del presidente Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

5. Astor entra nel campo immobiliare di New York grazie alla sua amicizia con Aaron Burr.

Sebbene si fosse occupato della speculazione immobiliare in precedenti occasioni, il primo grande affare di terra di Astor arrivò nel 1807, quando l'ex vicepresidente Aaron Burr fu arrestato per tradimento per il suo coinvolgimento in un complotto per annettere territori in Louisiana e Messico e stabilirvi una repubblica indipendente. Burr, che aveva già ipotecato la sua tenuta di Manhattan, nota come Richmond Hill, chiese aiuto ad Astor. Burr era stato assolto, ma la sua reputazione era in rovina e cercava un nuovo inizio in Europa. Alla disperata ricerca di denaro, accettò di trasferire l'atto di Richmond Hill ad Astor per soli $ 32.000, in quello che Burr in seguito sostenne doveva essere un accordo temporaneo. Astor, ovviamente, non vide nulla di temporaneo nella transazione. Nei successivi decenni avrebbe spartito centinaia di appezzamenti di terreno dall'ex tenuta Burr, negoziando contratti di locazione sempre più elevati con gli inquilini. Mentre la città di New York si espandeva verso nord, Astor vendette la sua terra già edificata per nuovi appezzamenti, seguendo i percorsi di costruzione dei servizi municipali come l'acqua e le linee di trasporto. Entro il 1830, Astor si era completamente ritirato dal business delle pellicce e dedicato il suo tempo alla vera impresa per fare soldi, il settore immobiliare di New York City.

6. Una biblioteca creata per volontà di Astor faceva parte del sistema della biblioteca pubblica di New York.

Quando John Jacob Astor morì nel marzo 1848, il suo testamento conteneva lasciti per diversi gruppi di beneficenza più circa $ 400.000 ($ 10 milioni di dollari di oggi) per la creazione di una biblioteca pubblica gratuita, da costruire in quello che oggi è il quartiere dell'East Village di New York. La Biblioteca Astor divenne una delle istituzioni più importranti della città, ma la mancanza di ulteriore sostegno finanziario da parte della famiglia Astor la lasciò in difficoltà finanziarie. Nel 1895, la collezione Astor si fuse con quella di un altro filantropo di New York, James Lenox, e utilizzando i fondi lasciati da un altro, l'ex governatore di New York Samuel Tilden, creò il sistema della biblioteca pubblica di New York. La biblioteca della filiale principale, sulla 42esima strada e sulla Fifth Avenue, è stata aperta nel 1911, e per più di un secolo l'ingresso è stato sorvegliato da due leoni di marmo, originariamente conosciuti come Leo Astor e Leo Lenox dai benefattori della biblioteca, ma ora più popolarmente noti come "Pazienza" e "Fortezza". La libreria Astor originale, nella parte bassa di Manhattan, fu infine acquistata dal Public Theatre, allora noto come New York Shakespeare Company, che ha prodotto centinaia di eventi teatrali presso il sito, tra cui la prima mondiale del musical rock "Hair", nel 1967.

7. Astor ha creato la prima "fiduciria" familiare nella storia americana.

A parte donazioni di beneficenza come la biblioteca, John Jacob Astor ha lasciato la maggior parte della sua fortuna di $ 20 milioni (stimata dalla rivista Forbes per un valore di oltre $ 100 miliardi di noggi), al suo secondo figlio, William Backhouse Astor, Sr. Per garantire la continuazione della ricchezza della sua famiglia, tuttavia, Astor pianificò con grande anticipo un'usanza che verrà utilizzata da altri magnati. Nel 1834, creò quello che si ritiene essere il primo trust familiare americano, costituito da 125 lotti di proprietà immobiliari di valore che coprono gran parte del lato ovest del centro di Manhattan. Il controllo degli Astor su una così vasta porzione di proprietà immobiliari di Manhattan ha portato alla coniazione di uno dei soprannomi della famiglia: i "proprietari di New York". Il trust fu sciolto in seguito alla morte dell'ultimo dei nipoti di John Jacob nel 1919, con più di una dozzina di discendenti di Astor che condividevano il guadagno finanziario. Tuttavia, un famoso Astor (Jacob IV) non godette per molto della sua eredità poichè morì nel Titanic nell'aprile del 1912.

John Jacob Astor to Thomas Jefferson, 14 March 1812 "Sulla collaborazione con i nativi americani".

From John Jacob Astor

- New York, 14 March 1812.

Sir,

I am induced to take the liberty of addressing you, from a belief that it will afford you some satisfaction to be informed of the progress which has been made in carrying on a trade with the Indians, which at it’s commencement was favoured with your approbation.

Since I had the pleasure of speaking to you first at Washington concerning it, my constant study has been to attain the object; and for this purpose I sent a ship in November 1809 to Columbia River, the captain of which had several times been there, and enjoyed both the esteem and confidence of the Indians. He took with him a cargo for trade, while in the mean time he was to prepare the Indians for a friendly reception to some white men who would come to stay with them. From thence he was to proceed to the Russian settlement, with a proposition to the Governor for the purpose of friendly intercourse and mutual benefit in trade.

In June 1810 I sent a party of men, say about seventy in number, to ascend the Missouri, with a view to make Columbia River and meet the people who had gone by water, as well as to ascertain the points at which it might be most proper to establish posts for trade, &c.

In September 1810 I sent a second ship to Columbia River, with sixty men and all the means which were thought necessary to establish a post at or near the mouth of that river.

In October 1811 I sent a third ship with above sixty men and all necessaries, to fix a post and to remain at or near Columbia River, and to cooperate with those who had gone before.

The first ship made her port, and from thence made a visit to Count Barranoff, Governor of the Russian settlements in North West America. My propositions met with attention, and I have received from him a letter approving of my plan; but for a final arrangement he referred to the Government and the Russian American Fur Company at St Petersburg. The ship made a voyage to Canton, sold her furs, and returned to Columbia River to meet the one which sailed in 1810, and to concert with her. I hope to hear from them in about three months.

The last account which I had of the party which ascended the Missouri was by letter of 17 July last, about 180 miles below the Mandan1 Village, where they left the Missouri, and took the Big River in a southern course, this being recommended as nearer and easier to the south branch of Columbia River than the route taken by Mr Lewis: they were well provided, and had procured near a hundred horses to transport their baggage.—The accounts as to ultimate success were fair and encouraging, and they had no doubt of meeting their friends who went by sea; which I think they must have done in October last.

In June 1809, when Mr Daschkoff was sent to this country, he was charged by his Government to remonstrate to ours against a trade carried on by citizens of the United States to the North West Coast, supplying the Indians with arms & ammunition, which not only afforded the means of killing one another with greater facility, but also endangered their own settlements.—As the Government could not well prevent this, I proposed a plan to Mr Daschkoff which it was thought would meet the end required, namely, an agreement between the American Fur Company of this country and the American Fur Company of Russia, that the former should supply the latter with all articles which they needed from this country and from Europe, (thus becoming their carriers &c) and to have an establishment at or near Columbia; but not to trade with natives near the Russian settlements, and by no means to supply them with arms or ammunition. On the other hand the latter not to deal with any transient traders or ships, nor with the natives at or near Columbia River. This plan was submitted to the Governor of the Russian settlements on the North West Course, who approved of it.

When Count Pahlen came to this country, he also was charged by his government to speak to our government on this Subject.2 I communicated the plan to him, who was so much pleased with it that he transmitted it to his Court. I sent a gentleman for this purpose to St Petersburg, who presented it to Count Romanskoff, who also is much pleased with it, but there exists some difficulty as to a condition which I had proposed, namely, that the Russian Government should allow the American Fur Company to carry their articles of fur from this country to Russia free of duty, or subject to a moderate duty only (at present they are prohibited). The Government seems well enough disposed to grant this, but it appears there was an engagement entered into between them and the Fur Company at the time of its formation, prohibiting the entry of furs except by the Russian Fur Company, who had not yet felt inclined to consent to the admission. There was however still some hope: to all the other propositions they were ready to agree. Should this plan succeed, I think we shall do very well as far as respects that part of our business.

With respect to our Trade on the frontier and in the Interior, I have not been so fortunate: on the contrary great and insurmountable difficulties are thrown in our way by the present restrictions on our commerce.

After negociating with the Michilimackinac Company for nearly three years to purchase them out, and not succeeding, I had determined to risk an opposition; and accordingly in October 1810 I ordered a quantity of goods from England for this trade, and made engagements with several Indian traders and others, to carry on the business. The people of Canada being informed of this, & knowing that an opposition would be very injurious, and at the same time seeing that I was determined to push one, they proposed to sell to the American Fur Company the property and establishments they had in the Indian country within the territory and boundaries of the United States, together with that at St Joseph’s, on condition that we should not for five years trade beyond those boundaries or in British dominions in opposition to them; and that for five years the trade within those limits should be carried on upon joint account. This agreement was completed, and by it the American Fur Company became possessed of the property before mentioned: but as the assortment of goods on hand at St Joseph’s, Michilimackinac and other places, was very incomplete for outfits in the interior, it became necessary to obtain a further supply, and we were in hopes that by some change in our political situation we might be enabled to bring in our goods which we had ordered from England, and which had been Transported to St Joseph’s (for in consequence of the President’s proclamation they had been shipped, though before the 2 Feby 1811, to Canada instead of New York.) But very unfortunately for us our expectations have not been realised. On application to the President in August last we were informed that Congress had left no power with the Executive to grant permission. The consequence has been, that the Indians have been very badly and not half supplied; and though in the mean while we have been under the necessity of retaining in pay the people we had engaged, as well as of keeping up all our establishments at the usual expense, yet we have been unable to carry our business to more than a fourth of it’s usual extent.

This dead expense is a serious loss to us, beside the interest on a stock on hand, chief part of which is unsaleable from want of other articles; while on the other hand the useful & saleable commodities lie locked up at Montreal and St Joseph’s. If we had only a part of them in the Indian country or at Michilimakinac, we could make out to keep the Indians3 contented, and keep the trade together in our own hands. But unless this is the case, we shall be under the necessity of selling our property to great sacrifice (as the articles are not saleable except for the Indian trade) either to the British agents for the Indian department of that Government, or to the Canada traders: thus totally relinquishing the trade to them.—

I have been thinking to apply to Congress for relief, at least to get permission to transport our property from the island of St Joseph to the Indian country within the territory or boundary of the United States.

Whether such application would be likely to meet with success, or whether in the present state of things it would be proper to make it, I have not been able to determine. I am so much embarrassed I know not what to do. It is probable that unless our Government do something by which the Indians may get their usual supplies (and which are not now to be had in the United States) there will be great uneasiness on their part, if not actual hostility: for they will become desperate by those privations: under which indeed they cannot exist.—

Perhaps, Sir, you will condescend to give some advice to me how to proceed. The Government, say the President and heads of Executive Departments, are well informed of the situation of the American Fur Company, as no step of importance has been taken without their previous approbation: they know of my plan with the Russians, as well as of my arrangements in the Interior.

The party which ascended the Missouri is under the direction of a very respectable gentleman from Trenton, New Jersey, by the name of Hunt.

The North West Company of Canada having received information of our intention to establish a post at Columbia, sent a party of forty men in 1810 from Lake Superior, with intent to be before us; but they were prevented by Indians in the Rocky Mountains from proceeding further, and were obliged to return. Another party has been sent in 1811 from the same place and for the same object, consisting of sixty men. We shall know next summer how far they have succeeded; at all events I think we must be ahead of them.

By what I can learn there is a great deal of fur on the west side of the mountains, and a considerable business is to be done on the coast with the Russians.

I am with Great Respect Sir your very Humble Servt,

John Jacob Astor

N.B. I will thank you To consider that part of my Comunication which relates to the contemplated4 arrangement with the Russians as Privet

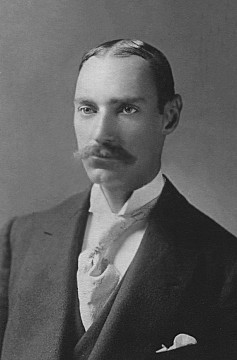

John Jacob Astor IV

E' nato a Rhinebeck, New York. Ha studiato alla St. Paul's School di Concord, nel Massachusetts. Fu accettato all'Università di Harvard, ma sembra che non si sia laureato. Viaggiò in Europa dal 1888 al 1891 prima di tornare in America per gestire i vasti interessi immobiliari della famiglia. È stato uno dei fondatori del Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, di cui era comproprietario con suo cugino, Willy Astor. Ha anche costruito l'Hotel St. Regis e l'Hotel Knickerbocker. Durante la guerra ispano-americana del 1898 fu nominato colonnello e donò il suo yacht, Nourmahal, alla causa americana, oltre ad equipaggiare una batteria di artiglieria da montagna.

Dopo aver divorziato dalla sua prima moglie ( Ava) nel 1909, due anni dopo (all'età di 47 anni) si sposò nella sala da ballo di Beechwood con la diciottenne Madeleine Force. La società era contrariata e per calmare le cose fecero un lungo viaggio in Europa. Durante il viaggio, Madeleine rimase incinta e poiché volevano che il loro bambino nascesse in America, tornarono negli Stati Uniti sullo sfortunato Titanic . Sua moglie incinta è stata salvata, ma John cedette il suo posto nella scialuppa di salvataggio a due adolescenti spaventati. È stato visto l'ultima volta fumare una sigaretta sul ponte con lo scrittore Jacques Futrelle. Ha lasciato una proprietà di $ 87 milioni.

John Jacob Astor IV

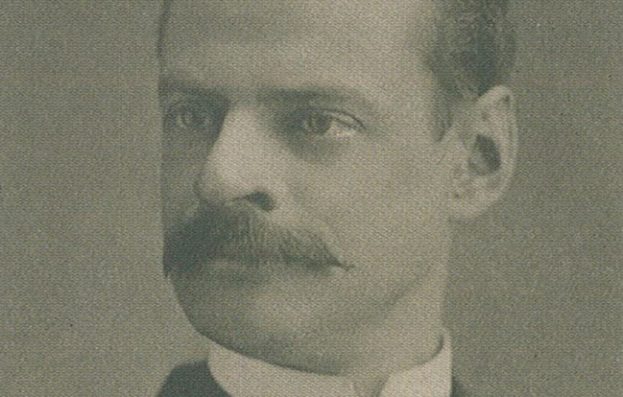

William Waldorf-Astor, 1848-1919

“…Certo è che mio padre è nato in un'età severa e che i suoi genitori erano rigidi nelle loro concezioni di giusto e sbagliato. Da bambino non gli era permesso fischiare, né leggere altro che libri religiosi la domenica… Spesso sentivo che aveva bisogno di aiuto e simpatia, eppure sembrava impossibile raggiungerlo attraverso le sue difese di riserbo e distacco…” Riflessioni della figlia di Astor su suo padre.

William Waldorf Astor nacque a New York City nel 1848 come unico figlio di John Jacob Astor III. Solo due generazioni prima, il bisnonno, John Jacob Astor I, aveva lasciato il villaggio di Walldorf, vicino a Heidelberg, nel sud-ovest della Germania, per trovarsi un futuro al di là dell'Atlantico. E che futuro ha trovato: dopo aver accumulato enormi profitti attraverso il commercio di pellicce e un vasto impero marittimo, ha investito i suoi soldi in proprietà sull'isola di Manhattan, guadagnandosi il titolo di "Landlord of New York".

Solo tre generazioni di sviluppo immobiliare dopo, il William Waldorf Astor di Two Temple Place faceva parte di una delle dinastie più ricche della storia degli Stati Uniti, ereditando una vasta fortuna nel 1890. Intervistando Astor a Two Temple Place per il suo libro del 1906, The Future in America , HG Wells ha scritto:

“…[William Waldorf Astor] estrae l'oro da New York con la stessa efficacia con cui un furetto estrae il sangue da un coniglio. "

Ma il rapporto di Astor con l'America era infelice e di reciproca avversione. Nel 1892, forse per scomparire dalla vista del pubblico, inviò un rapporto sulla propria morte ai giornali statunitensi, e fu ricompensato da necrologi poco gentili; il suo tempo negli Stati Uniti era davvero finito.

Emigrato in Inghilterra nel 1890, aveva presto acquistato Cliveden, la straordinaria casa di campagna del XVII secolo nel Buckinghamshire, così come la casa di famiglia di Anne Boleyn Hever Castle nel Kent, una casa a Brighton, e una sorprendente villa fronte mare a Sorrento. Ma è nella sua commissione per la costruzione di questo sontuoso ufficio nel centro di Londra che otteniamo un'idea degli interessi e delle aspirazioni di Astor. Ha consegnato al suo architetto, l'acclamato John Loughborough Pearson, un budget illimitato per Two Temple Place e il risultato si legge come una breve biografia di Astor, creata per lui da alcuni dei più grandi artigiani dell'epoca. La storia attesta un uomo timido e austero con una natura riservata e una personalità pungente, e questo si riflette nell'imponente facciata dell'edificio, nei formidabili doccioni e nella camera blindata originale - una volta sicura all'avanguardia con un pavimento in granito e personalizzato- ha realizzato la porta in acciaio Chubb che da allora è stata rimossa. Nel frattempo, un interno opulento con pannelli in legno e intricati intagli è un vivido riflesso delle sue passioni e interessi più profondi, con una fantasia di figure romantiche e storiche della letteratura classica, della mitologia e del passato. L'edificio è ricco di narrativa e contro-narrativa e premia al meglio i visitatori più ficcanaso!

“ Un incrocio tra un club londinese, una casa di campagna inglese e un college di Oxbridge… ”

A Londra, oltre al suo lavoro di amministrazione della tenuta di famiglia a New York, Astor acquistò una serie di giornali, in particolare per noi oggi The Observer nel 1911, che in seguito rimase in famiglia per oltre 70 anni. Astor fece notevoli donazioni filantropiche nel Regno Unito, e presumibilmente non è estraneo al fatto che fu nominato cittadino britannico nel 1899 e nel gennaio 1916 accettò un titolo nobiliare del Regno Unito con il titolo di Castello di Hever.

Si dice che il matrimonio di Astor sia stato senza gioia, sebbene lui e Mamie avessero quattro figli sopravvissuti per portare avanti la dinastia. Della famiglia Astor in America nel 18° e 19° secolo è stato ripetutamente detto che 'le mogli li hanno fatti', e garantire 'buoni matrimoni' per i loro figli e spingere la mobilità sociale dei loro mariti fabbricando la 'società' è un tema ricorrente in la nostra narrazione ricevuta di alcune delle principali donne Astor del XIX secolo. Altri Astor degni di nota includono, in seguito, l'incendiaria Nancy Astor che appare sulla scena nel 1906 e fu la prima donna in Parlamento, così come John Jacob Astor IV, cugino dell'Astor di Two Temple Place, che morì sul Titanic, in luna di miele con la sua seconda moglie, trent'anni più giovane di lui.

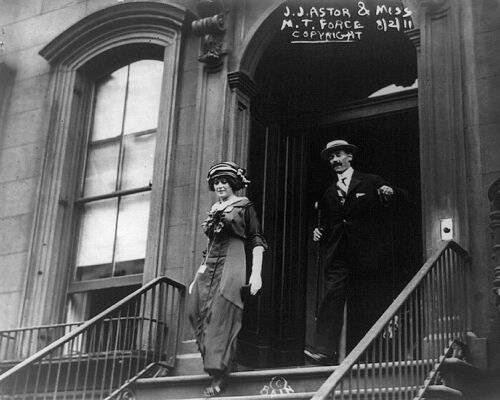

John Jacob Astor IV e Madeleine Force

Il Waldorf Astoria

Il Waldorf Astoria ha origine alla fine del 1800 dall’unione di due hotel, il Waldorf Hotel di proprietà di William Waldorf Astor aperto nel 1893 all’angolo tra la Fifth Ave. e 33rd St., su parte del terreno dove ora sorge l'Empire State Building e l'altro, l’Astoria Hotel, di proprietà di suo cugino John Jacob Astor aperto nel 1897.

Nel 1931 fu costruito l’edificio attuale su Park Avenue in stile Art Déco su progetto dello studio di architetti Schultze & Weaver. Quando fu inaugurato con le sue oltre 1.300 stanze e i suoi 47 piani per 191 m, era l’hotel più grande e alto del mondo. Aveva una propria piattaforma ferroviaria, Track 61, che faceva parte della rete della metropolitana ed era collegata alla Grand Central Terminal. Fu utilizzata tra gli altri dal presidente Franklin D. Roosevelt e dal generale Douglas MacArthur.

Nel 1949 fu acquistato da Conrad Hilton e nel 2014 rivenduto alla Anbang, società assicuratrice cinese per quasi 2 miliardi di dollari. Nel 2016 è stato chiuso per una grande ristrutturazione che durerà cinque anni e lo trasformerà quasi completamente in un residence di appartamenti di lusso. Quando riaprirà l’hotel avrà solo dalle 300 alle 400 camere.

Tantissimi gli ospiti illustri, primi fra tuti i Presidenti degli Stati Uniti in visita a New York. Ci sono poi stati la regina Elisabetta II e Filippo di Edimburgo, il Duca e la Duchessa di Windsor, il principe Ranieri III di Monaco e la principessa Grace Kelly, Charlie Chaplin, Ava Gardner, Liv Ullmann, Gregory Peck, John Wayne, Katharine Hepburn, Spencer Tracy, Muhammad Ali, Burt Reynolds, Robert Montgomery e molti altri.

Tra i film girati nell’hotel ci sono Grand Hotel Astoria (1945), Un provinciale a New York (1970), Broadway Danny Rose (1984), Il principe cerca moglie (1988), Profumo di donna (1992), Destini incrociati (1999), Terapia e pallottole (1999), Serendipity (2001), I Tenenbaums (2001), Un amore a 5 stelle (2002), Two Weeks Notice (2002), End of the Century (2003), Mr. and Mrs. Smith (2005), La Pantera Rosa (2006) e L'imbroglio - The Hoax (2006). Tra le serie televisive ci sono Law and Order, Rescue Me, Sex and the City, I Soprano e Will and Grace.

William Waldorf Astor was the only child of John Jacob Astor III

Caroline Astor,

During the Gilded Age, Caroline Astor, also known as The Mrs. Astor, reigned as the queen of New York society, and her parties were equally as famous.

If the name Astor sounds familiar, it’s because they're one of the most prominent family names found in New York history. The Astors, and specifically Caroline Astor, built what we now know as The Knickerbockers, the upper crust of New York’s society in the Gilded Age. From the 1870s until the 1900s, Mrs. Astor presided over thousands of parties at her opulent mansions on Fifth Avenue, only open to those she deemed worthy (later known as "The 400").

Papers at the time made a big to-do of Mrs. William Backhouse Astor’s (born Caroline Webster Schermerhorn) desire to be called The Mrs. Astor. She actually wasn’t the only Mrs. Astor, and her husband was only a second son, but that didn’t stop her from claiming the name.

Despite protests from her nephew Waldorf Astor (yes, that Waldorf), Caroline became The Mrs. Astor in NYC social circles. Hers was the only name on a calling card that gave you guaranteed entry to any elite event of the time.

You could only secure a spot at one of Mrs. Astor’s parties if you were one of “The 400” or “The Patriarchs,” a list of people referred to as The Knickerbockers by the likes of Washington Irving (though they didn’t like the name). These soirées were frequented only by those directly related to what Mrs. Astor and her ilk thought of as “Old New York.”

Old New York of course just meant old money that came from the Dutch and English settlers of the city—familiar names like Stuyvesant and Rhinelander—who made a substantial mark on Manhattan and its surrounding areas.

Along with Ward McAllister, Mrs. Astor decided on the 25 families—all with at least $1 million at the time, which amounts to over $20 million by today’s standards—that would be included at all fêtes, and required to bring at least four friends of the same caliber to each affair.

Mrs. Astor famously denied entrance to “New Money” families that earned their fortunes, like the Vanderbilts. Incidentally, her feud with Alva Vanderbilt only ended because Mrs. Astor’s daughter Carrie wanted to be invited to the Vanderbilt costume ball, but couldn’t go because Alva had never received a calling card from the Astors. Cracking under this pressure ultimately ended Mrs. Astor’s reign as the Queen of New York.

Decorum, upheld mostly by women of the day, was of utmost importance to Mrs. Astor. There could be no talk of “legs” (or any body parts at all, for that matter) at one of her parties. And don’t even think about being alone with a member of the opposite sex. That was expressly forbidden.

Men, of course, were granted more liberties, and frequently held mistresses or visited brothels in what is now Murray Hill. Mrs. Astor, for her part, politely declined to notice.

Mrs. Astor was given a very fine education for a lady of her day, brought up by nannies and governesses, attending an elite private school, and frequently making trips to Europe, where she learned what it really meant to be a member of the aristocracy.

Her party guests were permitted to talk to her about the weather, etiquette, languages, and even gossip slightly at the goings-on.

Mrs. Astor’s parties were a glorified marriage mart for the wealthiest people of the day. You’d attend if you were looking to settle down with a powerful other half—or find a match for your offspring—and expand your fortune and influence.

The Caroline Astor home wxas at Fifth Avenue. . The house was built in 1893.

No other avenue in New York housed as many well-to-do people as Fifth Avenue at the turn of the century. Wealthy people kept building up the street, higher and higher, ultimately residing on what is now the Upper East Side.

Mrs. Astor had two houses on Fifth Avenue, one in the 30s and one in the 60s, after the 30s became “too downtown” for her and her family.

Mrs. Astor’s most famous residence at 350 Fifth Avenue was a New York staple, but she would never have guessed the address’ significance today.

When she vacated her home near what is now Herald Square, it became the second half of the Waldorf-Astoria, which was later torn down to build The Empire State Building. The joint hotels moved uptown to their current location.

MRS.

One of the biggest causes of New Yorker envy today centers around square footage, but Mrs. Astor never had to worry about that. Her joint houses (which she shared with her only son John Jacob Astor the IV and his family—he would later die on the Titanic) would both be thrown open for parties, able to admit over 1,000 guests for balls.

Inside her cozy abode you’d find peacock feather rugs, an art gallery that doubled as the ballroom, and even several nude female statues.

The one thing you wouldn’t want to do at a Mrs. Astor party would be to out-shine Mrs. Astor herself. Case in point: this old-money society queen wore a black velvet gown with a white jet and tulle shoulder knots, topped with her famous diamond tiara and necklace to one party thrown at her Upper East Side mansion.

Ritratto di Caroline Astor. Introdusse il rito dei grandi ricevimenti a New York.

La guerra tra i “Robber Barons” per la conquista degli Hotel di Manhattan

Dal New York Times: “Evoca visioni di titanici monopolisti che schiacciavano i concorrenti, truccavano i mercati e corrompevano il governo”. Ora, sono abbastanza sicuro di sapere a chi state pensando… ma trattenetevi! Questa citazione è del 9 febbraio 1859 e si riferisce ai “Robber Barons”, egocentrici uomini d’affari spietati, senza scrupoli e smisuratamente ricchi, che si intrattengono educatamente tra loro e nel contempo si scontrano brutalmente per denaro e potere. Gli uomini dell’Empire State, ovvero, Rockefeller, JP Morgan, Gould, Vanderbilt, Carnegie e Astor modellarono New York come capitale dell’Impero, la nuova Roma.

La famiglia Astor costruì la sua ricchezza grazie al commercio di pelli di castoro (e traffico illegale di oppio), reinvestendo poi i profitti nel settore immobiliare di New York. La stazione della metropolitana di Astor Place esibisce ancora le piastrelle con il castoro come simbolo originale della New York olandese e della famiglia Astor. Tra i grandi doni che gli Astor hanno lasciato alla città c’è la New York Public Library e un patrimonio di grandi alberghi, mentre i newyorkesi, in loro onore, hanno chiamato “Astoria” un quartiere nel Queens.

L’Astor House, sulla Broadway e Vesey St

Astor House fu il primo hotel di lusso, oramai dimenticato, di New York. Costruito nel 1836 vicino alla St. Paul’s Chapel, occupava l’intero isolato su Broadway tra Vesey Street e Barclay Street, ed era il favorito dai potenti e ricchi dell’epoca. Essendo poi di fatto anche la sede del partito Whig (precursore del Partito Repubblicano) ebbe come clienti il Presidente Abraham Lincoln e il suo Segretario di Stato William Seward, il quale visse all’Astor House per trent’anni. L’hotel fu demolito nel 1926, ma non prima di aver ospitato circa diciotto presidenti degli Stati Uniti da Andrew Jackson a Theodore Roosevelt, più di qualsiasi altro hotel negli Stati Uniti. Gli Astor si spostarono poi a nord, costruendo il Waldorf-Astoria, il Knickerbocker e l’incredibile Astor Hotel a Times Square (demolito nel 1967).

“Hai cercato di truffarmi, non ti denuncerò… ti rovinerò”. Eccoci di nuovo. So a chi pensate che appartenga questa citazione, ma non ci siamo ancora. Appartiene infatti dello spietato tiranno Cornelius Vanderbilt, “Il Commodoro”, potente patriarca della famiglia Vanderbilt. Dal punto di vista degli Astor, i Vanderbilt erano dei nouveau riche, ma non potevano essere ignorati perché la loro fortuna, accumulata con le spedizioni e le ferrovie, li rese la famiglia più ricca d’America. Oggi, bisognerebbe sommare la ricchezza di Bill Gates e Jeff Bezos per eguagliare la fortuna dei Vanderbilt.

Il St. Regis Hotel, costruito da John Jacob Astor IV .

Il Knickerbocker Hotel costruito da John Jacob Astor IV

Si racconta che nel 1901, gli Astor stavano costruendo un altro elegante hotel, il St. Regis, di fronte alla Chiesa Presbiteriana sulla Fifth Avenue all’incrocio con la 55ma strada. Questo fece infuriare i Vanderbilt che volevano impedirgli di costruire un hotel commerciale a pochi isolati dalla loro magione (se allora si lamentavano che il St. Regis fosse un male, oggi avrebbero avuto di fronte la Trump Tower). I Vanderbilt contavano su una legge di New York che proibiva il rilascio della licenza per la vendita di alcolici a qualsiasi attività la cui entrata fosse a meno di 200 passi da una chiesa. Per ovviare, gli Astor spostarono quindi l’entrata principale dell’hotel, dalla Fifth Avenue alla 55° strada rientrando quindi in conformità con le norme. A quel punto, Rockefeller, un altro “nouveau riche, kid on the block” venne in aiuto dei Vanderbilt e comprò un palazzo vicino al St Regis, cosicché gli Astor avrebbero perso i 2/3 dei voti di maggioranza necessari da parte dei vicini per assicurarsi la licenza. In risposta, gli Astor comprarono una casa adiacente per mettere in minoranza il voto congiunto dei Rockefeller e Vanderbilt e, in aggiunta “comprarono” anche un senatore dello Stato di New York che cambiò la legge in modo da esentare tutti gli hotel con più di 200 stanze, incluso il St. Regis. Su sa che per vincere a Monopoli bisogna piazzare gli hotel nelle strade più importanti.

Mentre John Jacob Astor IV espandeva il suo impero alberghiero a New York, i Vanderbilt erano impegnati a reinventare la città con la creazione della magnifica Grand Central Station, un progetto che non ebbe eguali fino alla costruzione del Rockefeller Center di John D. Rockefeller alla fine degli anni 30. William Gwynne Vanderbilt aprì il Vanderbilt Hotel, ora adibito a condominio, su Park Avenue e 31a strada, un elegante edificio in stile Adam dove lui occupava l’ultimo piano. L’unica parte rimasta originale è il ristorante che si affaccia su Park Avenue ancora decorato con le piastrelle originali di Guastavino. Amici e rivali, gli Astor e i Vanderbilt hanno condiviso un tragico destino. John Jacob Astor IV morì nel naufragio dell’RMS Titanic nel 1912 e William Gwynne Vanderbilt (che inizialmente era prenotato sul Titanic, ma cambiò idea all’ultimo minuto) morì tre anni dopo con l’affondamento dell’RMS Lusitania.

I Vanderbilt circondarono il terminale di Grand Central con una serie di grandiosi edifici e hotel, da est con l’hotel Biltmore, soggetto di una famosa battaglia legale ( persa) per ottenere lo status storico. Il Roosevelt, lo Yale Club e il Chatham hotel, che spari insieme alla zona pedonale Chatham Walk. Da ovest invece l’Intercontinental Barclay e l’elegante Commodore Hotel (ora Grand Hyatt). Nel 1977 il Commodore era sull’orlo del collasso quando il costruttore Donald Trump promise alla città di “salvarlo”; al contrario, “l’avido, avido, avido” Trump, come lo definì il sindaco Ed Koch, coprì l’elegante facciata con un dozzinale vetro verde riflettente, distrusse gli interni e la sala da ballo e riuscì a “strappare” alla città l’abbattimento delle tasse di 400 milioni di dollari per i successivi 40 anni.

Il Commodore Hotel dietro Grand Central

Fred Trump fece fortuna speculando nel settore immobiliare nel Queens, e suo figlio Donald Trump seguì le orme del padre, mentre Harry Helmsley, proprio come il padre Fred, creò un impero immobiliare a Manhattan. Tuttavia verrà ricordato più per la sua tirannica moglie Leona Helmsley, soprannominata “the Queen of mean” ( “la regina della cattiveria”) che per essere stato il proprietario dell’Empire State building.

Quando la Queen of Mean incontrò il Mean del Queens, ( “il cattivo del Queens”) fu odio a prima vista.

Leona era responsabile degli hotel Helmsley, che consistevano a quel tempo in una varietà di alberghi stile anni 70 esteticamente sgradevoli, il New York Helmsley sulla 42a strada (ora Westin) e l’Helmsley Midtown, mentre L’Helmsley Palace (ora Lotte Palace) è composto da due parti: la storica casa Willard costruita nel 1882 e progettata in stile rinascimentale su ispirazione del Palazzo della Cancelleria a Roma da McKim, Mead and White e l’orribile ampiamento in stile Darth Vader costruita da Harry Helmsley. E infine il Park Lane Hotel, dove è difficile decidere se sia più brutto, l’esterno in stile post-moderno degli anni 70 o l’interno kitsch stile Luigi XIV. Tuttavia la vista su Central Park è mozzafiato. Anni fa ho visitato l’appartamento di Leona Helmsley, che si estendeva per tutto l’ultimo piano dell’hotel; era gigantesco, compreso il suo armadio, tanto che per la prima volta in vita mia ho fatto fatica ad uscirne.

Dopo un’aspra rivalità con Helmsley derivata dal loro accordo d’affari finito male sull’Empire State Building e sul St Moritz Hotel, Trump mise le mani sull’iconico Plaza Hotel (che fece fallire e rivendette con una perdita di 83 milioni di dollari) vicino al Park Lane. Trump definì Leona una “disgrazia per l’industria e una disgrazia per l’umanità in generale”. Una volta, a un evento, il “sofisticato” Trump versò un’intera bottiglia di vino nel cappuccio del cappotto di Leona. Leona era anch’essa un incubo negli affari, ma si rivelò particolarmente crudele e tirannica con i suoi dipendenti. Una volta disse ad una sua cameriera: “Noi non paghiamo le tasse; solo i miseri pagano le tasse”, tuttavia questa frase le procurò una condanna a diciannove mesi di carcere per evasione fiscale. Senza alcuna ironia Trump disse a Leona: “Non sarai più in grado di licenziare a caso e abusare delle persone per tuo sollazzo personale”. Leona dichiarò “Non crederei a Donald Trump se la sua lingua fosse autenticata da un notaio”.

Ad oggi, Trump gestisce solo il placcato finto-oro, Trump Central Park Hotel dopo che il suo nome venne tolto dall’ex Trump SoHo il quale è stato poi stato velocemente ribattezzato Dominick hotel.

I Robber Barons della “Gilded Age” hanno dato a Gotham cultura, arte e tesori architettonici inestimabili creando hotel che sono ancora l’invidia del mondo e valgono milioni, tutta un’altra storia con i finti albergatori.

Waldorf Astoria Hotel

Giova osservare che quasi tutti i grandissimi imprenditori USA furono anche grandissimi mecenati e che il loro nome più che associato alle imprese è legato ai loro lasciti testamentari in favore dell'umanità. Essi non solo hanno fatto grande l'America ma hanno gettato i semi della cultura statunitense. Le grandi dinastie del capitalismo americano: gli Astor, i Carnegie, i Mellon, i Frick, i Rockefeller, i Merrill, i Morgan, i Guggenheim, i Walton, i Disney, i Cargill, i Bloomberg, i Giannini, i Johnson, gli Huntington, gli Stanford vedono nella filantropia culturale una forma di restituzione (give back) alla comunità di parte di ciò che essi hanno ricevuto.

Eugenio Caruso

- 12 dicembre 2022

Tratto da